EXTRA GENTLE YOGA FOR FIBROMYALGIA

ABOUT FIBROMYALGIA

Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) comes from the Latin root words: “fibro,” meaning connective

tissue fibers, “my,” muscle, “al,” pain, and “gia,” condition of. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate

Dictionary defines “syndrome” as “a group of signs and symptoms that occur together and

characterize a particular abnormality.”

Dr. William Balfour of the University of Edinburgh first described FMS in 1816. For many

years the medical profession had various labels for FMS, including chronic rheumatism,

myalgia, pressure point syndrome, and fibrositis. Often viewed as a psychological condition, in

1987, FMS was finally recognized by the American Medical Association as a true illness and a

major cause of disability.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Due to its varied symptoms, diagnosis of FMS can be challenging. Symptoms can include:

difficulty sleeping, loss of hearing, blurred vision, falls, itching, pelvic pain, soft tissue aches and

pains, and irritable bowel syndrome. Many people with FMS ill complain of fatigue and nonrestorative

sleep and say, “I hurt all over.”

An official diagnosis for FMS was the result of the Copenhagen Declaration establishing

fibromyalgia as an officially recognized syndrome on January 1, 1993, for the World Health

Organization. (See, www.cmq.org/fibroang.pdf.

) The Declaration defines FMS as a painful,

non-articular condition predominantly involving muscles and as the most common cause of

chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain. The Declaration also states that FMS is “part of a

wider syndrome encompassing headaches, irritable bladder, dysmenorrhea, cold sensitivity,

Raynaud’s phenomenon, restless legs, atypical patterns of numbness and tingling, exercise

intolerance and complaints of weakness.” People with FMS often suffer from depression and

anxiety. Not surprising with all the possible physical symptoms.

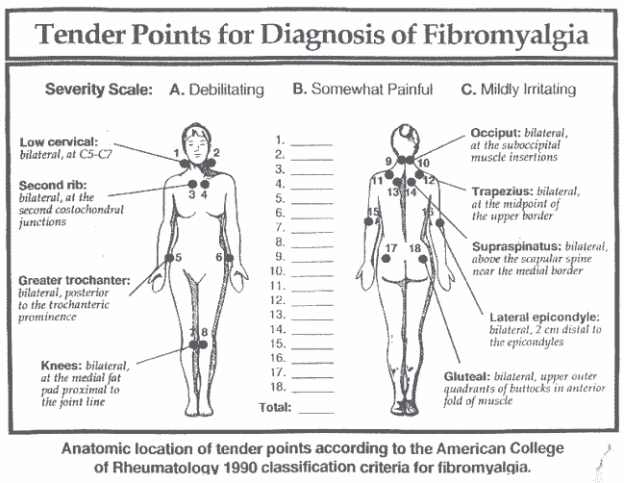

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology defined the points of FMS and the World

Health Organization considered the definition as suitable for research purposes. The following

symptoms were then added to the official diagnosis criteria: “ . . . the presence of unexplained

widespread pain or aching, persistent fatigue, generalized morning stiffness, non-refreshing

sleep, and multiple tender points. Most patients with these symptoms have at least 11 tender

points. But a variable proportion of otherwise typical patients may have less than 11 tender

points at the time of the examination.” The Copenhagen Declaration definition states that you

must have at least 11 of 18 specified tender points to be diagnosed with FMS. The pressure used

to test for pain should be enough to whiten the thumbnail when pressing on the points.

RESEARCH AND STUDIES SUPPORT COMPLEMENTARY TREATMENTS

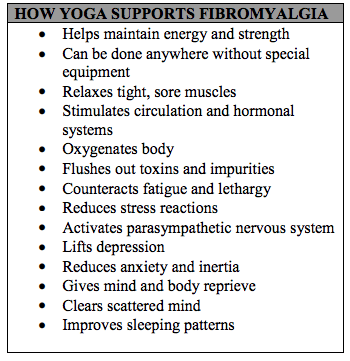

According to scientists at the University of Missouri-Columbia, “Patients with fibromyalgia

syndrome (FMS) who exercise and practice relaxation and other non-drug techniques report

fewer symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and morning stiffness than do patients who receive

medication alone. * * * Optimal treatment of FMS should include non-pharmacological

interventions, specifically exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy, in addition to appropriate

medication management as needed for sleep and pain symptoms,” says Lynn A. Rossy, M.A.,

head of a study that made these conclusions. (See, www.news.wisc.edu/packages/emotion.

)

Another study found meditation helps to quiet the mind and better deal with pain of symptoms

and is an effective way to distract oneself from symptoms. (See, www.healthcentral.com/news.

)

A study of 18 men and women who had persistent pain for more than three months indicates

Yoga may help those with chronic pain. Participants attended 90-minute Yoga sessions three

times weekly for 30 days. All 18 patients either experienced some kind of improvement or

remained the same. No symptoms increased. (See, www.healthcentral.com/news.

)

The theory of visualization bringing a positive outcome was supported by a study demonstrating

that people can increase muscle power simply by imagining themselves doing the exercises.

Guang Yue led this study at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation’s Lerner Research Institute. (See, http://straitstimes.asia1.com.sg/health/story/0,3324,91956,00.html

)

FROM PAIN TO YOGA

Debra Risberg, a Kripalu certified teacher in Illinois, developed FMS 31 years ago at age 16.

Debra says, “It was devastating physically and emotionally and the doctors we turned to for help

only made things worse by putting me in a painful brace and plying me with tranquilizers to keep

me from complaining.” Debra was not given an official diagnosis of FMS until 1987.

A search for freedom from pain led Debra to Yoga. After her Kripalu teacher left town in 1995,

she became a certified Yoga teacher. Since then Debra has opened her own studio and teaches

students with FMS and chronic pain as well as the general public. When asked how having this

condition affects her ability to teach Yoga, she responded, “It helps me to be more sensitive to

moving slowly into postures and surrendering to find the deepest release for myself and my

students. It keeps me humble. It reminds me of what is truly important because I can't afford to

waste precious energy.”

Debra’s class for people with FMS includes gentle and restorative yoga, meditation, deep

relaxation and group support. She said, “The group support model I have used involves breaking

up into couples or triples and doing co-active listening. Students seem to love that part of the

class.”

Debra continued, “You can't apply the same methods to everyone. Some people are so ill and

disabled that they can hardly move or stand to be touched. Others can be quite athletic and love

deep tissue massage. It depends on the personality, the genetic makeup and how the illness

manifests in each individual. Pranayama is also important but something like kapalabhati can be

too strong.”

Allowing students to relax and breath into sensations can bring an understanding of pain.

Meditation teaches one to stop reacting to intense sensations and to begin a more supportive

relationship with the body.

For asana practice Debra includes isometrics to release muscles in specific areas. She offers

breathing techniques such as the three-part breath, ujayii, and alternate nostril.

Debra hesitates to make diet recommendations because each person is unique in their needs. She

did say, “I had no pain when I was in India living on a fresh vegetarian diet. I think the

medicinal properties of the spices and herbs in Indian vegetarian cooking are good for me. Also,

the food there had no additives or chemicals on it.” Although there is no scientific proof to

support the theory, Debra suspects, “[FMS] may be caused by environmental toxins combined

with stressful living conditions.” Debra also takes a daily Ayurvedic remedy called Tryphala to

help the digestive tract.

THE AUTHOR’S EXPERIENCE

Most of my life I have dealt with pain in some area of my body. Symptoms included soft tissue

injuries, structural imbalances, insomnia, chronic illness, general fatigue and depression.

In 1996 some of my symptoms were given the label of FMS. The diagnosis itself was not

especially comforting, as there is no known cure for FMS; however, knowing that there were

others who had this condition, and that the medical community recognized it, was promising. I

wasn’t crazy!

An introduction to Yoga twelve years ago taught me that breathing into sensations can create

detachment from (and an acceptance of) symptoms. Gained awareness of daily movements and

use of ergonomics in the workplace helped the pain subside. A new attitude toward life led to

the desire of sharing this ancient tradition with others. It wasn’t just the physical movement of

the asanas -- meditation, visualization, pranayama, and deep relaxation brought a greater sense of

knowing my true self. Yoga has been one of the most effective tools for healing. However, it is

not a panacea and should be used as an adjunct with other treatment approaches.

I became a certified teacher through Integrative Yoga Therapy in 1998.

Regular study with teachers who focus on

therapeutic applications of Yoga and

healing of the whole continue to guide me.

After initial training with teachers of

Iyengar and other styles of Yoga, I

discovered the tradition of T.K.V.

Desikachar (sometimes referred to as

Viniyoga in the United States).

Appropriate sequencing and adaptations of

poses to meet individual needs, conscious

linking of breath and movement, together

with specific pranayama practices, sound,

and deep relaxation, has brought profound

levels of healing to me, and my students as

well.

Two qualities must be present in asana

practice: stability and alertness (sthira) and

comfort (sukha). (See, Yoga Sutra II.46.)

Students should not push muscles to point

of exertion. When one is unable to perform asana repetitions, suggest mentally visualizing the

performance of the movement. Holding poses for too long can cause symptom flare-ups as

contracting a muscle for any period of time can activate trigger points. Movement should not be

excessive although immobility is another fairly common cause of trigger point flare-ups. Pauses

between repetitions allow muscles to relax. Asana practice should always end with a rest in

savasana or another restorative posture.

Everyday posture and body mechanics are especially important. How one stands, lifts, sits,

walks, and moves can play a big role in sustaining daily energy. If the body is out of balance,

strain can result. Avoid sitting in one position for lengthy periods of time as muscle contraction

can occur. The body needs to move. Check your body’s alignment often throughout the day

Yoga Nidra practice, also known as body scan, can be effective for healing. Resting deeply

without falling asleep restores the mind and body. (See, www.nondual.com.

) Integrating regular

periods of rest into each day, even when you feel well, may prevent flare-ups.

Suggested pranayama techniques include: langhana (lengthening the exhalation) for cleansing

the body, sitali (the cooling breath) to promote healing of autoimmune deficiencies such as FMS,

and nadi sodhana pranayama, (alternate nasal breathing) to bring balance to bodily systems.

Each individual is different and has unique needs; therefore, choosing pranayama techniques to

meet those needs is important.

Meditation has been proven to help with chronic pain and depression. By stopping thoughts

momentarily, the mind and body experience a rejuvenating break. Sleep patterns and drug

dependency may improve as well.

For teachers who struggle with FMS, reducing or eliminating demonstration of poses may help

conserve energy needed for healing. This is a beautiful way to practice ahimsa toward self.

Refraining from demonstrating can also encourage students to move inward and experience the

poses more fully in their own bodies.

Working with a teacher who has therapeutic training and experience is essential. Begin with an

extra gentle practice. Remember the line often quoted by seasoned teachers, “If you can breathe,

you can do Yoga.” With conscious breathing and simple movements a calming peace can

replace fatigue and frustration. Take it easy and listen to your inner wisdom.

Bio

Jeanne Dillion has been the owner of Yoga for Wellness and Back to Basics (an office

ergonomics and workplace wellness consulting business) since 1998. She is certified through

Integrative Yoga Therapy and a Registered Yoga Teacher. Jeanne has been practicing Yoga

since 1990, and has attended trainings with T.K.V. Desikachar and Jon Kabat-Zinn.

Jeanne recently released a CD and audiocassette, Extra Gentle Yoga, appropriate for students

with FMS and other debilitating conditions. To purchase, go to www.yogaforwellnesspro.com

or e-mail her at jeannedillion@cableone.net.

A fibromyalgia workshop for Yoga teachers with Debra Risberg will be offered at the Kripalu

Yoga Teachers Association Conference October 24 – 27, 2002. Call Kripalu for details.

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READING

Bouanchaud, B: The Essence of Yoga, Reflections on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, Portland, OR:

Rudra Press, 1997.

Davis, M, Eshelman, ER, McKay, M: The Relaxation & Stress Reduction Workbook, Oakland,

CA: New Harbinger Publications: 1995.

Desikachar, TKV: The Heart of Yoga, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1995.

Desikachar, TKV: The Viniyoga of Yoga, Chennai, India: Quadra Press Limited, 2001.

Feuerstein, G: The Yoga Perspective on Pain, Mental Health, and Euthanasia, Pain and Pain

Management, www.iayt.org/news.php

, pp. 3-5.

Kabat-Zinn, J: Full Catastrophe Living New York, Delta; 1990.

Kraftsow, G: Yoga for Wellness, Arkana: Penguin Group, 1999.

Lasater, J: Relax and Renew: Restful Yoga for Stressful Times, Berkeley, CA: Rodmell Press:

1995.

Miller, R: The Journal of the International Association of Yoga Therapists, The

Psychophysiology of Respiration. 1991.

Miller, R: Experiencing Nonduality with Richard C. Miller, Ph.D., www.nondual.com

LePage, J: Integrative Yoga Therapy Training Manual. Aptos CA, Printsmith, 1994.

Starlanyl, Devin, Copeland, ME, Fibromyalgia & Chronic Myofascial Pain Syndrome A Survival

Manual, Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.: 1996.

Salt, WB, Season, EH: Fibromyalgia and the Mind Body Spirit Connection 7 Steps for Living a

Healthy Life with Widespread Muscular Pain and Fatigue, Columbus, OH: Parkview

Publishing: 2000.

RESEARCH STUDIES

www.news.wisc.edu/packages/emotion

Measuring the power of positive outlooks. Looks at

people with fibromyalgia. www.cfah.org/hbns/newsrelease/nondrug8-31-99.cfm

Non-Drug Techniques Help Reduce

Symptoms of Fibromyalgia. www.healthcentral.com/news

Fibromyalgia improves over time; exercise helps 9/18/2001.

Yoga may help those with chronic pain 8/22/01. http://straitstimes.asia1.com.sg/health/story/0,3324,91956,00.html

People can increase muscle

power simply by visualizing themselves doing exercise. www.cmq.org/Fibroang.pdf

College des medecins du Quebec guidelines for fibromyalgia.